And into the Forest I Go, to Lose My Mind and Find…More Brewing Yeast!

Scientists isolated yeast from a Finland forest to identify strains that could be useful in making non-alcoholic beer

Sometimes nothing beats an ice cold beer on a hot day. My guess is that many people feel this way as beer is one of the most consumed beverages in the world and making beer is a billion dollar (US$) industry. Beer typically contains alcohol, but there are also non-alcoholic (NA) versions, which alone also produce billions of dollars of revenue. The demand for NA beer has been skyrocketing in recent years, as people look to healthy alternatives for weight management and avoiding the unhealthy effects of alcohol. This makes streamlining the production of NA beer and reducing the substantial costs to produce it a major goal to many people. In a recent study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, a group of scientists approached this problem by looking for new brewing yeast from the wild!

But you may be wondering, why would scientists take this type of approach? What would it solve? Well, let me explain. Beer is produced from the fermentation of sugars in grains by fungi called yeast [like the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a.k.a. brewer’s yeast or baker’s yeast]. One way to make NA beer is by removing the alcohol produced after fermentation. This can be done by high-tech processes like vacuum distillation, membrane filtering, or reverse osmosis. The unfortunate thing about these processes is that they are quite costly making it difficult for smaller scale brewers to invest in the equipment needed.

So, what are cheaper alternatives? One alternative is by changing the length or style of the fermentation process. Another, is by using different yeast species that do not produce much alcohol as a byproduct of fermentation, such as the commonly used species (for over a century), Saccharomyces ludwigii. However, for regular beer, different alcohol producing yeast species or strains* are used depending on the type of beer being brewed (e.g. lager uses bottom fermenting yeast in a cold environment whereas ale uses top fermenting yeast in a warm environment); so, it would be nice to have plentiful choices in low-alcohol producing yeast strains for NA beer production as well. This is especially true because the perception of NA beer flavor being close to its alcohol containing counterpart is critical to consumers and NA beer can sometimes be viewed as having off flavors. Simply put, the more choices in yeast for the brewer could mean more choices in flavor for the consumer. That is why scientists are interested in alternative species or strains that could offer different and/or better brewing options.

*note: the term species refers to yeast different from each other in the same way as humans differ from chimpanzees. The term strain refers to different individuals from the same yeast species, in the same way two humans differ.

One species that has been studied and is showing promise is a Basidiomycota yeast called Mrakia gelida. A unique feature of this species compared to other low-alcohol fermenting yeasts is that it is psychrophilic, or cold temperature loving, whereas many others are mesophilic, or moderate temperature loving. This means M. gelida does not grow at room temperature making it easier to maintain brewery hygiene while using it. Additionally, brewing at low temperatures is an important feature in the production of certain beers and brewing at low temperatures can reduce contamination, which is a problem for NA beer production (one reason being that the sterilizing effect of ethanol does not occur). So, with this species being a promising candidate, scientists from the recent study aimed to isolate new strains of M. gelida from the wild and test their brewing capabilities and usefulness relative to the reference species S. ludwigii.

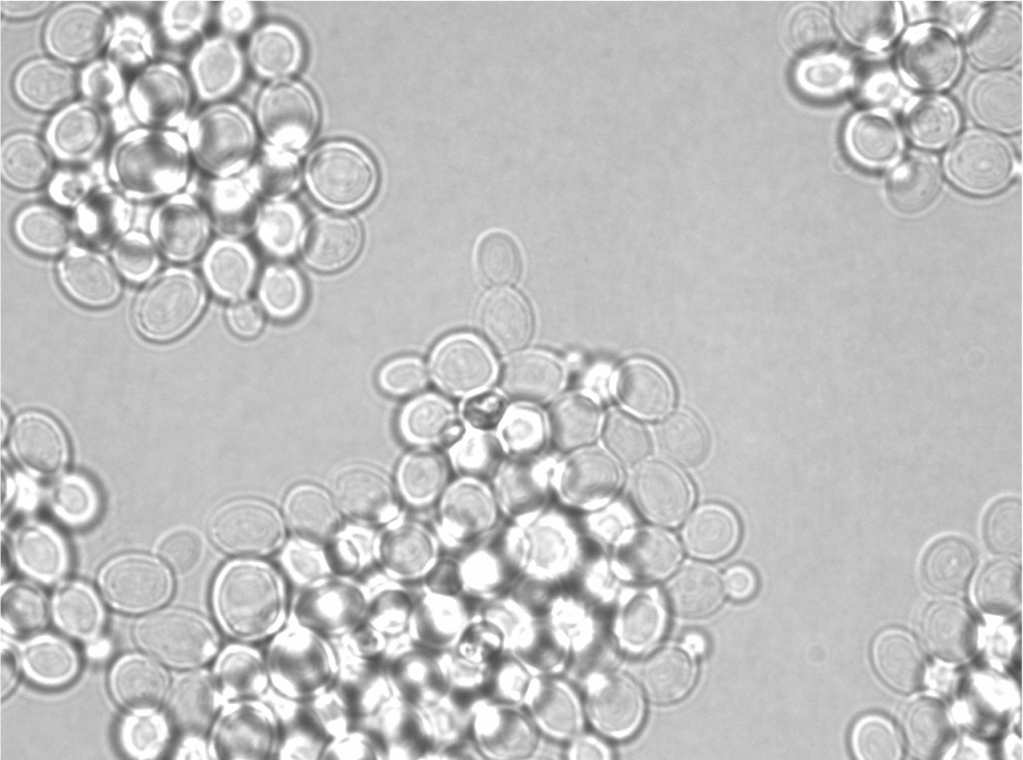

The natural habitat of several yeasts is considered to be forests, so if one wants to isolate new yeast they have to head to the woods. During a larger survey in 2019 the scientists embarked to find yeast from tree bark in the Punkaharju forests in Finland. Twelve yeast strains were isolated and the scientists used sequencing techniques of the ITS gene region (a region frequently used to speciate fungi) for phylogenetic analysis, which identified the strains were indeed M. gelida.

They compared these different strains of M. gelida to the reference species S. ludwigii for fermentative traits including alcohol levels produced, flavor volatile production, and their viability after fermentation (to know if the strains can be ‘repitched’ or used again in the brewing process). There were some differences found between species considered both good and bad, however, overall, all the M. gelida strains showed similar fermentative profiles, produced beer with an average of ~0.7% alcohol (<0.5% is the target), showed good viability for repitching, and had some level of desirable flavor active compounds present.

Next, the scientists picked the M. gelida strain that showed the best fermentative and flavor compound profile to further compare to S. ludwigii by upscaling production that ended with bottled beer that could undergo sensory testing. Sensory testing was performed by seven professionals using the DLG scheme (see specific details in the figure legend below). By this method, both species met the requirements for a usable flavor profile and showed some differences in their aroma profiles. Overall M. gelida showed a clean flavor profile representing a solid base beer worthy of further development.

In regards to safety and hygiene, the scientists performed experiments to test the safety of this species for human handling and consumption. Pathogenic yeast (or yeast that cause infections) like the species Candida albicans have specific qualities that allow it to cause yeast infections in humans, including its ability to form stress tolerating biofilms or grow at human body temperature (37℃). The scientists found that M. gelida poses a lower risk for biofilm formation than S. ludwigii and S. ludwigii can slightly grow at 37℃ whereas M. gelida cannot. The scientists also tested common preservatives, disinfectants, and antifungals and found that M. gelida is not resistant to any of them. They also note that no M. gelida infection has ever been documented in humans. So, this organism seems to have an extremely low risk for brewery operations, brewers, and consumers, but further approval will be needed.

Overall, the scientists showed that fermentation with M. gelida is a potentially safe and low cost method for producing NA beers. Its unique quality of tolerating cold temperatures can make it a great species to have available for many brewers and diversify their yeast toolkit. I think it is worth noting the importance of this type of exploratory research as well. Studying natural diversity of yeasts can be quite beneficial as it may uncover unknown traits in wild strains that greatly benefit the brewing process. There is so much diversity still left unexplored. So let’s keep exploring. Who knows how many yeast species great for brewing (and other applications) aren’t even discovered yet!

Leave a comment