Let’s Talk About Sex Baby, Let’s Talk About Mechanosensory!

Scientists uncover a novel role for a mechanosensory ion channel in the sensing of sexual stimulation of the genitals

Humans think about sex – a lot. It has captured the imagination of humanity for thousands of years due to all of its joyous sensations. But have you ever wondered where those sensations come from? What is occurring in your body at the cellular level in response to sexual stimulation? How does your body know to get aroused? Well, in a recent study in the journal Science, a group of researchers advanced our understanding in this area by uncovering how one gene (PIEZO2) contributes to sexual arousal by sensing gentle stimulation to one’s genitals. These findings could have important ramifications for human health as they may lead to therapeutics that help individuals with sexual dysfunction. But before we dive into the new findings about PIEZO2, let’s first look at what was previously known about the gene.

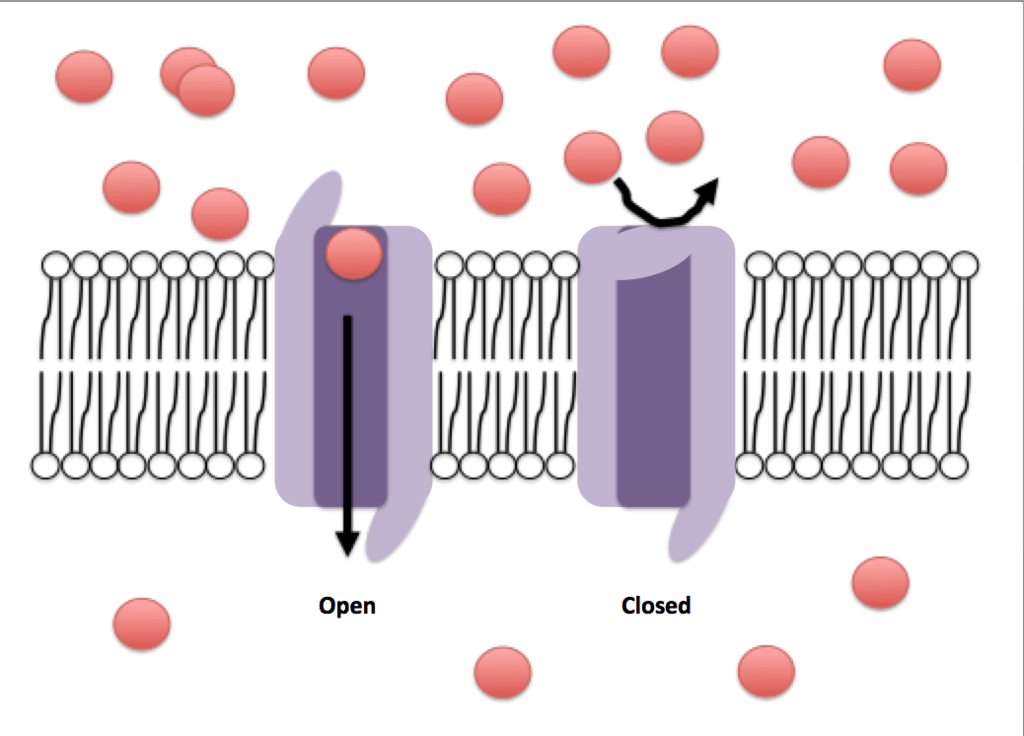

In a study from 2010, scientists discovered the PIEZO2 gene encoded a protein that acts as a component for a mechanosensory ion channel. Mechanosensory ion channels are proteins in the cell membrane that can open and close in response to mechanical signals (e.g. pressure) to allow for the passage of ions into the cell. This ion flow creates an electrical signal that excites the cell and triggers a response to the stimulus (e.g. like sending a signal to our brain to create a sensation). This overall process is referred to as mechanotransduction and is responsible for many types of sensory in mammals, including touch, pain, hearing, proprioception, and the adjustment of blood flow. Studies since the discovery of PIEZO2, such as one done with mice in 2014 or one done on humans in 2016, have revealed that one of the gene’s major roles is in sensing gentle, non-painful touch in multiple regions of the body.

However, compared to our understanding of mechanosensing in other parts of the body (e.g. hands), our relative understanding of mechanosensing in our genitals has remained less clear. Specifically, how mechanosensory triggers physiological responses that ultimately lead to sexual pleasure is unclear. That is why the researchers from the recent study set out to explore what role PIEZO2 might play in mechanosensing in the genitals during sexual stimulation. To address this question, the scientists developed both microscopy imaging and behavioral experiments in mice. One of the behavioral experiments used von Frey filaments, which are plastic filaments of ranging size or stiffness that can be pressed to an area (like the mouse’s back paw) to create a non-harmful sensation and test for a withdrawal response. Depending on which size filament induces a response, a sensory threshold can be determined.

To start the experiment, the scientists first tested in several mice each of the mouse’s back paw and perineum (i.e. area between the anus and genitals) with the filaments to identify sensitivity differences between the two areas. Both areas were found to be similarly sensitive to more intense stimulation by the filaments or painful stimulation by a pin prick, but the perineum was clearly much more sensitive to light stimulation than the paw. They tested what role PIEZO2 played in the perineum sensitivity by generating mice that do not express that gene in the perineum. These mutant mice showed a drastic loss in sensitivity to the filaments in the perineum, though they did not show a change in sensitivity to the painful pin prick. This experiment highlighted the specific role of PIEZO2 in sensing gentle touch sensations in the perineum area.

In the next experiment, the researchers performed extensive fluorescence microscopy imaging of nerve cells (i.e. neurons) in anesthetized mice to visualize and quantify the activity of neurons in the perineum and back paw in response to different stimuli (i.e. air puff, brush, vibration, and pinch). Simply put, this method allowed the scientists to visually see if a neuron ‘fires’ in response to a stimulus. This method showed neurons responsible for sensing in the perineum showed higher sensitivity than neurons responsible for sensing in the back paw as they required far less stimulation to be fired, and this sensitivity was largely diminished in cells that lacked PIEZO2. Therefore, these results matched the conclusions made by the behavioral experiments above.

So, because the scientists showed that PIEZO2 is required for the sensory of gentle stimulation of the genitals, they presumed that typical mating responses may be compromised in mutant mice that did not express the gene in the perineum. They tested this hypothesis and found that, although the mice were still interested in mating, mice lacking PIEZO2 expression in their perineum mostly failed to mate. The mutant males were unable to appropriately obtain erections upon physical stimulation and the females would often take on a sit-rejection posture at the time when introgression (i.e. the insertion of the penis into the vagina) should occur. That is why it’s no surprise that the scientists further found that mating pairs where one mouse had PIEZO2 disrupted had no pups while healthy mating pairs had many litters over six months. So overall, the scientists found that the ion channel PIEZO2 is critical for gentle-touch mechanosensory in mice genitals and successful mating.

Now, you may be wondering how translatable is this to humans? The scientists were also curious and therefore had clinical interviews with a small group of five people [three males and two females] that contain a rare genetic variant causing a loss-of-function of the PIEZO2 gene. Ideally, a larger sample size of people would have been interviewed, but that proved difficult because it is a rare genetic variant in humans. Nonetheless, these people reported having hyposensation in their genitals. One of the males even allowed quantitation similar to the mouse experiments, which showed that he had far less sensitivity to vibration and von Frey filaments compared to typical healthy males. These individuals still reported being sexually active and able to be aroused by videos, erotic thoughts, or genital stimulation, however, they had delayed, attenuated, or absent physiological responses to light stimulation, and clinical diagnoses of hypo-orgasmisa in the males and anorgasmia in the females. So, just like in the mice, humans with improperly functioning PIEZO2 still show a desire for sexual intercourse, but there are difficulties with carrying out the process.

In summary, the scientists revealed that the gene PIEZO2 in mice is important for sensations in the genitals, for causing physiological responses for copulation, and for reproductive success, and this most likely translates well to humans. I think for the behavioral experiments with the von Frey filaments it would have been interesting to also test sensitivity in mice lacking PIEZO2 expression in the back paw to have a direct behavioral comparison of its role in the perineum versus the paw. Does removal of PIEZO2 in both tissues make them have the same sensitivity? Is PIEZO2 the main reason for their differences?

Regardless, these findings are important and could be applicable to human health, as they suggest the development of topical medicines that inhibit or enhance PIEZO2 function could help with individuals that suffer from hypersensitive or hyposensitive genitals, respectively. Moreover, I think it is easy to agree that there is value in any advancements that teach us about the molecular mechanisms of sexual pleasure, as these advancements create a deeper connection to a fundamental aspect of life that humans have pondered about since the beginning of time.

Leave a comment