Natural Genetic Variation Reveals Surprises About A Fungal Pathogen

Scientists find that a well-studied fungal gene (i.e. EFG1) involved in pathogenesis does not behave the same in all strains of the common yeast pathogen Candida albicans

Many fungi can be harmless, or even beneficial to other organisms, but some choose a killer lifestyle. Pathogenic fungi (or fungi that cause infections) can wreak havoc and have led to the destruction of crops, decimation of frogs, and devastation of bat populations. They will come after humans too. So, it is no surprise that scientists want to understand how fungal pathogens grow, behave, and cause infections.

One of the major causes of fungal infections in humans is a single-celled yeast called Candida albicans. This fungus is the culprit of common yeast infections (called candidiasis), such as oral thrush or vaginal yeast infections. It is normally a commensal organism (or one that can coexist without causing harm) in our gut, mouths, and vaginas but can become pathogenic when people enter an immunocompromised state. Intense infections by this organism (often through sepsis) can even lead to death. That is what makes studying the genetics of this organism so important. However, due to limited capabilities at first, a fair amount of the initial research in this organism comes from only one specific clinical strain [a.k.a isolate or a clonal population of yeast]. This has had a limiting effect on our understanding of pathogenesis more broadly. Over the last fifteen years, scientists have begun taking a different approach by looking at the differences between diverse clinical strains, which has revealed surprising differences among individuals.

In a study from 2009, scientists found diverse C. albicans strains show differences in their ability to cause infections (referred to as virulence) in mouse models partly linked to differences in gene expression across the genome. Then, in a study from 2015, other researchers found that different clinical isolates showed striking differences in the structure of their genomes, including mutations and changes in the copy number of some genes, and even some strains contain extra copies of entire chromosomes. These genomic differences seemed to play a role in the differences between growth and virulence of some strains. One strain even showed a mutation in a gene that acts as a critical regulator of pathogenesis, EFG1, which drastically reduced the strain’s virulence! These works were a strong sign that looking at natural variation across clinical isolates could help understand how different strains may adapt to the host environment and possibly identify new gene variants and regulatory processes involved in pathogenesis. Then, in a study in 2019 and more recently in 2022, scientists looked more specifically at the functional differences of the gene EFG1 across different clinical isolates and found more surprises.

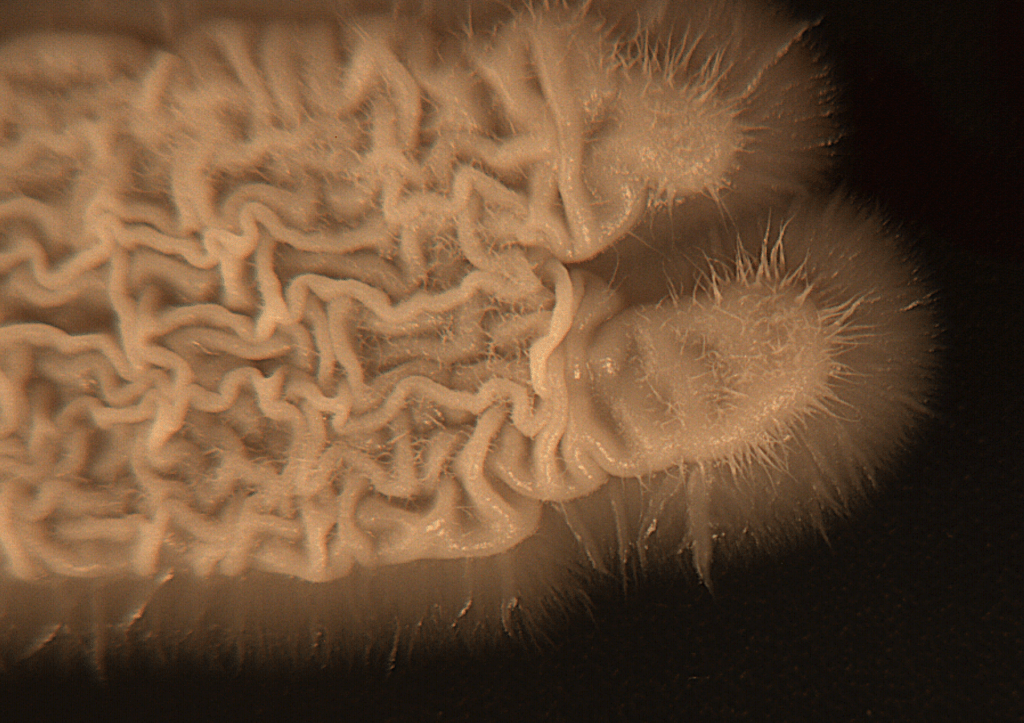

EFG1 encodes a transcription factor, which is a protein that regulates gene expression (meaning it can turn other genes on and off). This gene in particular is involved in turning on genes that are involved in switching C. albicans cells between growing in a round shape (called yeast-form) to growing in long filaments (called hyphae) referred to as filamentous growth. Filamentous growth allows C. albicans cells to penetrate host tissues and reach the bloodstream, where they can disperse to other sites in the host. Another pathogenic behavior EFG1 regulates is biofilm formation, which is when cell adhesion is increased to cause single cells to stick together and form a multicellular community that are more resistant to the host immune system and fungicidal drugs.

In the more recent studies, the researchers looked at gene expression levels related to EFG1 regulatory targets between different C. albicans strains. They found these targets showed differences in expression depending on the strain. In other words, a subset of genes regulated by EFG1 in one strain appeared to not necessarily be regulated by EFG1 in the other strains tested. This suggested transcription factor/target relationships can vary among C. albicans isolates.

Traditionally when transcription factors regulate gene expression, they do so by binding to the promoter of a gene (a regulatory segment of DNA upstream of a gene) to turn expression up or down. In theory, if EFG1binds to the promoter of different genes in different strains, it could explain why gene expression varies across individuals. However, this was not the scenario found by the same group of scientists in their 2022 study published in the journal mBio. In this study, they used a molecular technique to identify the genes EFG1 binds to across the genome and found the EFG1 binding profile was similar across strains, revealing that EFG1 is not binding to different genes. So then how does EFG1 cause the differences across strains?

Well, the study further showed that three other genes within the larger genetic network (i.e. transcription factors: BRG1, WOR1, and TEC1) that regulate their own genetic targets were the culprits. These genes showed differences in their own expression across strains and were affecting the way EFG1 was regulating its targets without affecting where it was binding. This finding adds a new layer to our understanding of how this important gene is regulating biological processes related to pathogenesis. More broadly, this means the scientists showed that the function of a well understood gene can behave differently across individuals and lead to surprising differences in phenotypes (i.e. physical attributes) based on the influences of other genes within its network.

Why are these findings important? One, these works have made significant contributions that will likely help pave the way to better understandings of fungal pathogenesis and the ways in which fungal pathogens can adapt to diverse environments. More broadly, and what I find to be most important, is that these works reveal an aspect of biology that is important to keep in mind for all biologists – that is – how useful natural variation can be to uncover new understandings of gene function and regulatory processes, even for systems that are thought to be well understood. This major theme is likely applicable to many other organisms and genetic circuits as well, beyond fungal pathogens, including genetic networks studied in humans. It will be interesting for similar studies to be done in other well characterized gene networks and organisms to see what new secrets natural variation can continue to reveal. Biological processes we believe are well understood may still hold many surprises.

Leave a reply to Paul Cullen Cancel reply